|

|

|

@orlandofiges |

|

|

| Home | |

| Bookstore | |

| Bio | |

| News | |

| The Europeans | |

| Revolutionary Russia | |

| Just Send Me Word | |

| Crimea | |

| The Whisperers | |

| Natasha's Dance | |

| Interpreting the Russian Revolution | |

| A People's Tragedy | |

| Peasant Russia | |

Just Send Me Word: A True Story of Love and Survival in the Gulag | ||||

|

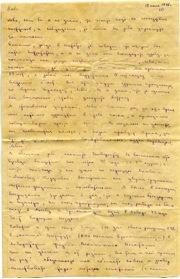

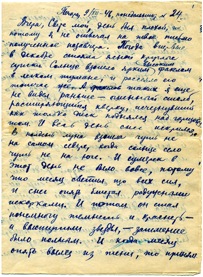

From the Front Inside Cover: Just Send Me Word is the extraordinary love story of two Muscovites, Lev and Svetlana. Kept apart for fourteen years by the Second World War and the Gulag, they stayed true to each other and left behind them an astonishing monument to their love: a remarkable cache of 1,500 letters exchanged between them as Lev battled to survive in one of Stalin’s most notorious labour camps. Smuggled in and out of the camp by workers and officials, these uncensored, beautifully written letters have a shocking immediacy, and allow us into the interior world of two people. Svetlana's letters are a testament to constancy and hope, even in the grey world of post-War Moscow. Lev’s, composed with care and tenderness, are torn between a wish to reassure Svetlana, and the desire to create an enduring record of the terrible conditions into which he had been thrown. Each one of these writings could have been his last. Orlando Figes tells Svetlana and Lev's story with remarkable insight and warmth, brilliantly reconstructing the broader world in which their narrative unfolded. Our historical understanding is enhanced by their letters, the only known real-time written record of life in Stalin's Gulag, but, as importantly, we are gripped by the story of a couple who, swept along by historical events, keep their devotion alive. As this extraordinary book shows, even in the worst of times and places, love, dedication and hope could triumph. Here, in the preface to Just send Me Word, Orlando Figes describes finding the letters: Three old trunks had just been delivered. They were sitting in a doorway, blocking people's way into the busy room where members of the public and historical researchers were received in the Moscow offices of Memorial. I had come that autumn of 2007 to visit some colleagues here in the research division of the human rights organization. Noticing my interest in the trunks, they told me they contained the biggest private archive given to Memorial in its twenty years of existence. It belonged to Lev and Svetlana Mishchenko, a couple who had met as students in the 1930s, only to be separated by the war of 1941-45 and Lev's subsequent imprisonment in the Gulag. As everyone kept telling me, their love story was extraordinary. We opened up the largest of the trunks. I had never seen anything like it: several thousand letters tightly stacked in bundles tied with string and rubber bands, notebooks, diaries, documents and photographs. The most valuable section of the archive was in the third and smallest of the trunks, a brown plywood case with leather trim and three metal locks that clicked open easily. Nobody could say how many letters it contained - we guessed perhaps two thousand - only how much the case weighed (37 kilograms). They were all love letters between Lev and Svetlana written while he was a prisoner in Pechora, one of Stalin's most notorious labour camps in the Far North of Russia. The first was written by Svetlana in July 1946, the last by Lev in November 1954. They were writing to each other at least twice a week. This was by far the largest cache of Gulag letters ever found. But what made these letters so remarkable was not just their quantity: it was the fact that nobody had censored them. They were smuggled in and out of the labour camp by voluntary workers and officials who sympathized with Lev. Rumours about the smuggling of letters were part of the Gulag's rich folklore but nobody had ever imagined an illegal postbag of this size. The letters were so tightly packed I had to wedge my fingers between them to get the first one out. It was from Svetlana to Lev. The short address read: Komi ASSR '274-11b' were bureaucratic figures of terrible significance. I began to read her neat handwriting on the yellow paper that crumbled in my hands. 'So here I am, not even knowing what I should write to you. That I miss you? But you know that. I feel I am living outside time, that I'm waiting for my life to start, like an intermission. Whatever I do, it seems like I'm just killing time.' I took another letter from the same bundle. It was one of Lev's. 'You once asked whether it's easier to live with or without hope. I can't build any kinds of hope, but I feel calm...' I was listening to a conversation between them.

Leafing through the letters, my excitement grew. Lev's were rich in details of the labour camp. They were possibly the only major real-time record of daily life in the Gulag that would ever come to light. Many memoirs of the labour camps by former prisoners had appeared, but nothing to compare with these letters, composed at the time inside the barbed-wire zone. Written to explain to his sole intended reader what he was going through, Lev's letters became, over the years, increasingly revealing about conditions in the camp. Svetlana's letters were meant to support him in the camp, to give him hope, but, as I soon realised, they also told the story of her own heroic struggle - against external obstacles and forces in herself - to keep her love for him alive. Perhaps 20 million people, mostly men, endured Stalin's labour camps. Prisoners, on average, were allowed to write and receive letters once a month, but all their correspondence was censored. It was difficult to maintain an intimate connection when all communication was first read by the police. An eight- or ten-year sentence almost always meant the breaking of relationships; girlfriends, wives or husbands, whole families, were lost by prisoners. Lev and Svetlana were exceptional. Not only did they find a way to write and even meet illegally, an extraordinary breach of Gulag rules that invited severe punishment, but they kept every precious letter, even those which put them at greatest risk, as a record of their love story. There turned out to be 1500 letters in that smallest trunk. It took over two years to transcribe them all. They are the documentary basis of Just Send Me Word, which also draws from the archive in the other trunks, from extensive interviews with Lev and Svetlana, their relatives and friends, from the writings of other prisoners in Pechora, from visits to the town and interviews with people who live there, and from the Gulag archives of the labour camp itself. Just Send Me Word is available on Amazon |

© 2011 Orlando Figes | All Rights Reserved